Karl Marx’s writings on Ireland are often overshadowed by his better-known work on capitalism. But in a remarkable 1867 report—delivered to German workers in London—Marx offered a powerful, layered analysis of colonialism in Ireland. In their detailed paper, Eamonn Slater and Terrence McDonough uncover Marx’s broader theory of colonialism as a complex social process, not just a capitalist one.

💭 What You’ll Learn from This Paper

Reading this paper gives you:

- 🧠 A deeper understanding of how colonialism worked in Ireland, beyond the usual economic theories.

- ⚖️ Insight into how political and legal systems supported colonial power, especially through landlord control.

- 🌱 Knowledge of how colonialism impacted the environment, introducing one of the earliest examples of ecological analysis (the “metabolic rift”).

- 📊 A case study in multi-layered oppression—economic, legal, social, and ecological—all interconnected.

- 🔄 A way to rethink modern colonial studies, moving past narrow “dependency theory” into a more nuanced framework.

- 📖 Context for how these ideas influenced Marx’s other works, including Capital.

This is more than just history—it’s a theoretical lens that helps us understand how empires operate and how resistance forms within complex systems.

🔍 Key Insights from the Paper

1️⃣ Colonialism as a Shifting Regime

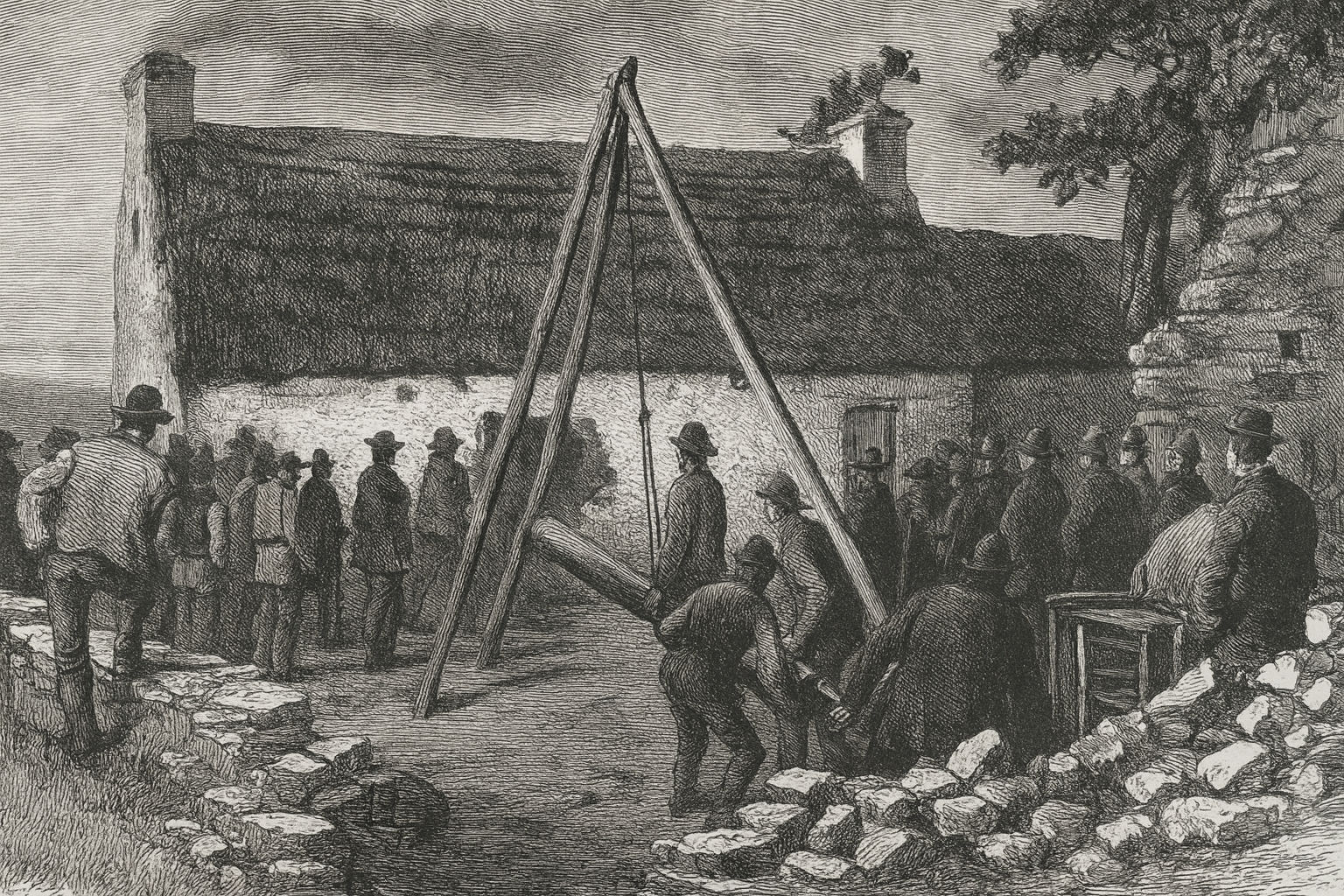

From Cromwell’s violent Plantations to the post-Famine “clearing of estates”, British rule evolved through phases—not a static system.

2️⃣ Feudalism, Not Capitalism

Ireland wasn’t colonised to advance capitalism—but to entrench a feudal landlord class. Landlords exploited tenants through rack-rents and legal systems.

3️⃣ Underdevelopment and Deindustrialisation

British rule crushed Irish manufacturing, pushing people back onto poor land—preparing the ground for the Great Famine.

4️⃣ Ecological Destruction: The ‘Metabolic Rift’

Marx links colonialism to environmental collapse. Exporting crops drained Ireland’s soil—a forgotten side of imperialism.

5️⃣ Impact on Body and Mind

Malnutrition, emigration, and ecological stress led to a rise in physical and mental health issues among Ireland’s poor.

6️⃣ Revolution as Response

The Fenian movement wasn’t just nationalism 🇮🇪—it was a resistance against deep systemic oppression.

💡 Conclusion

This overlooked report shows Marx wasn’t just a theorist of capitalism—he saw colonialism as a multidimensional regime that shaped society from top to bottom. Slater and McDonough’s paper revives that vision, offering an essential read for anyone interested in:

- Colonialism studies

- Irish history 🇮🇪

- Marxist theory

- Environmental sociology

- Social justice frameworks