Irish Metabolic Rifts – Marx and Engels on Ireland

Dr. Eamonn Slater

‘The concrete is concrete because it is the concentration of many determinations, hence the unity of the diverse’. (Marx – Grundrisse)

This website is concerned with an attempt to reconstitute the conceptual work of Marx and Engels on Ireland and specifically their endeavors to understand the complex relationships that existed between society and nature in this Irish social formation.

To do this, I want to focus on the presence of the concept of the metabolic rift, which John Bellamy Foster has recently attributed to Marx, within their Irish writings. I believe it is a critical theoretical microscope that allows us to examine the complex fluid interconnections that exists between nature and society. The forensic ability of the metabolic rift is achieved by its double form (Marx), in which the organic forms of nature metabolize with the social form that is especially prevalent in the social process of cultivation.

However, I also have applied the concept of the metabolic rift to help explore the essential structure of the contemporary suburban front garden in three articles. In this section, I hope to display the versality of the concept beyond agricultural cultivation.

Finally, I want to demonstrate that the metabolic rift within the writings of Marx and Engels is not exclusively confined to the Irish soil structure but also manifests itself in the individual metabolisms of the peasantry and the Irish population as a whole (work in progress).

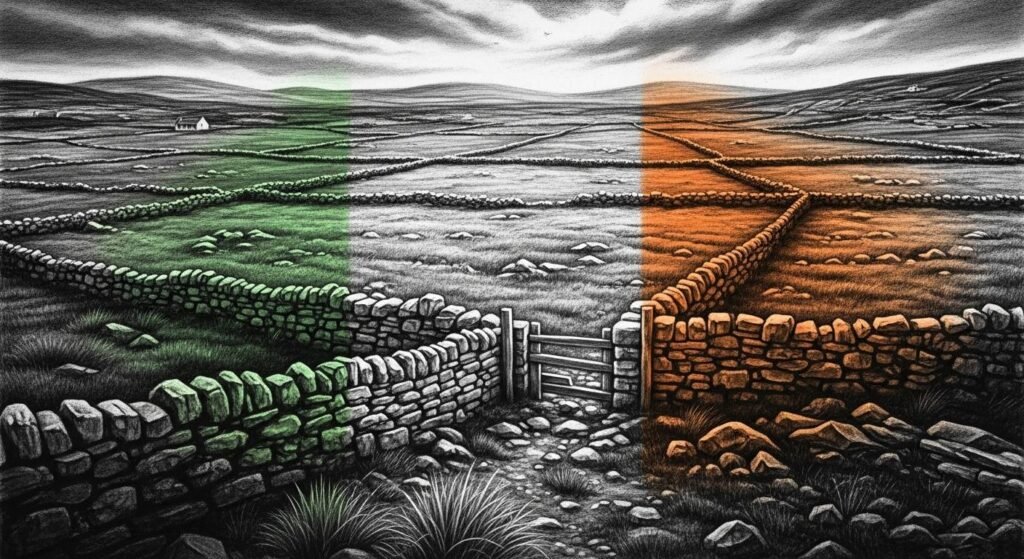

Marx on the colonization of Irish soil

This the centrepiece of the website, in which I attempt to explicate Marx’s understanding of British colonization of Ireland, with specific attention to how the Irish soil was ‘rifted’ of its constituents by that same social process of colonization.

To achieve this elucidation, it was necessary to follow the logic of Marx’s arguments as presented in his December 1867 speech on the Irish Question in London. The logic of his analysis is dialectical and it is in this format that he discussed the emergence of the metabolic rift in the context of colonial Ireland in the nineteenth century.

Exploring the social and organic forms of the Irish metabolic rifts.

Marx on nineteenth century colonial Ireland: analyzing colonialism as a social process

This article, which I co-wrote with Terrence Mc Donough, is survey of Marx’s insights, both empirical and conceptual, on colonial Ireland in his December 1867 speech. Therefore, it is a good entry point to the following pieces.

The most innovative aspect of Marx’s analysis is to perceive colonialism as a social process which penetrates all levels of the Irish social formation including the ecological, where Marx begins to explore the emergence of the colonial metabolic rift.

Marx on colonial Ireland: the dialectics of colonialism

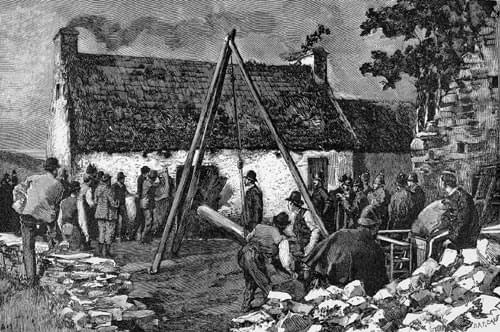

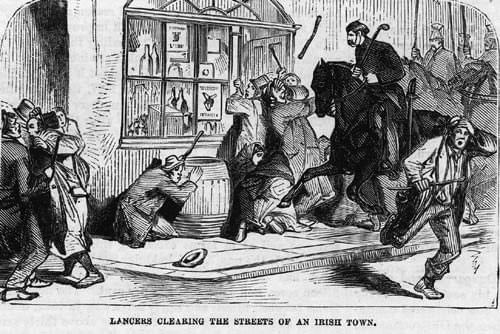

This article examines how Marx used his dialectical method of inquiry to unfold how colonialism was a social process that not only dominated all aspects of Irish society but that process evolved over time as Marx suggests in the following:

‘England has subverted the conditions of Irish society. At first it confiscated the land then it suppressed the industry by ‘Parliamentary enactments’, and lastly, it broke the active energy by armed force. And thus England created those abominable ‘conditions of society’ which enable a small caste of rapacious lordlings to dictate to the Irish people the terms on which they shall be allowed to hold the land and live upon it’ (Marx, Irish Question, 1971, p. 61).

Engels on Ireland’s dialectics of nature

This is my examination of Engel’s analysis of a concrete case study of nature’s organic/ecological mediating processes. Accordingly, it is the only time that Marx or Engels discussed in detail the specifics of ecological relationships within a particular eco-region.

Why Engels examined these Irish ‘natural conditions’ is that he was concerned how they function for agricultural cultivation. Going beyond the extensive data and statistics presented the conceptual trajectory of Engels’ investigation is to emphasise the inherent fluidity, mutual interaction and ‘universal connection’ of the dialectical forces of nature.

As “Nature Works Dialectically”, explicating how Engels and Marx analysed climate and climate change dialectically.

This piece is the conceptual culmination of my research on the Irish metabolic rift in general. Here, I propose that Engels and Marx conceptualize concrete reality, including nature, as dialectically determined.

In bringing together their diverse insights on climate and climate change and especially Engel’s in depth analysis of the Irish weather system, we can grasp how they perceived climate as the predominate determining process not only within organic nature but also within society’s cultivation processes. If we accept the idea that concrete reality is dialectically determined, we have to re-examine causation in this dialectically determined world.

Marx’s and Engel’s writings on colonialism and Ireland’s ecological conditions

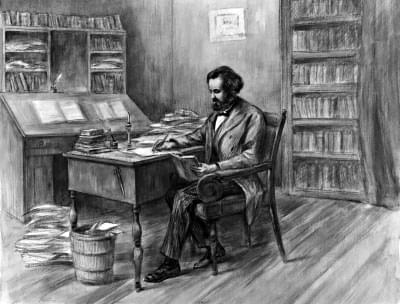

Notes for an undelivered speech on Ireland

On 26th November 1867, Marx was to give a talk to the First International meeting but due to ill health he did not talk on the Irish Question. However, he wrote a small outline for this meeting (6 printed pages) which this is a reproduction.

Although short and much of it written in note form, it does highlight his use of a dialectical method of investigation especially by his utilisation of the concepts of process and system and how those entities change over time.

Report of a speech by Marx

This is the document that Marx used to present his speech on the Irish Question, on December 16th 1867 (14 printed pages) to the German Worker’s Educational Association in London.

Within, the structure of the argument appears to be determined by his use of the dialectical method of exposition, where Marx Identifies colonialism as the predominate determinant of this Irish organic totality. Colonialism dominated not only the colonised Irish but also the soil they cultivated, giving rise to the colonial metabolic rift.

Eccarius’ summary report of Marx’s speech on Irish Question

Johann Georg Eccarius was a member of the General Council of the International who took notes of Marx’s speech in order to prepare them for publication, but it was never published. In which Eccarius proposed that Marx ‘proved that all attempts of the English government to anglicise the Irish population in past centuries had ended in failure’.

The significance of this summary lies in that it allows us to observe the overall trajectory of Marx’s analysis of the Irish Question, highlighting his main points of his presentation and reproducing some the concepts and expressions that Marx used in the speech.

Engels on the Natural conditions of Ireland

Engel’s draft of his History of Ireland was to consist of four chapters, which he worked on at the end of 1869 and during the first half of 1870. Only chapter one appears to be completed, which he entitled – Natural Conditions.

But its inclusion at the beginning of the text is critical as its supports an earlier assertion that Marx and Engels made about the correct way to write history: ‘The writing of history must always set out from these natural bases and their modifications in the course of history through the action of man’. (Marx and Engels, CW, vol.5, 1976: 31).

Rundale Agrarian Commune: Marx and Engels on primitive communism in Ireland and its metabolic rifts.

Rundale Agrarian Commune: Marx and Engels on primitive communism in Ireland and its internal dynamics.

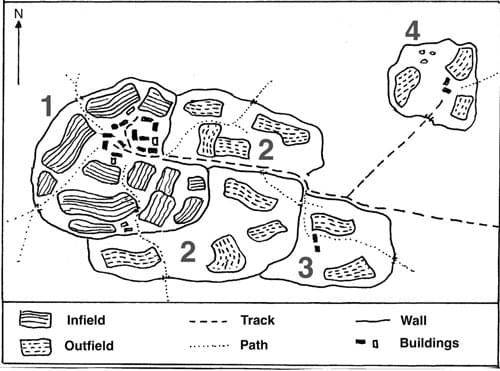

With Marx’s concept of the primitive communist mode of production we (with Eoin Flaherty) were able to account for the emergence in Ireland of a particular socio-ecological metabolism which created a metabolic rift in the agricultural ecosystem of the rundale agrarian commune. And the specific characteristics of this rundale socio-ecological metabolism were the increasing penetration of individualism over the various communal aspects of the rundale system.

This itself was ‘fueled’ by the inability of the commune to cope with its own population growth which was determined by its inability to expand spatially. These levels of determination formed a complex unity, which we needed to unravel in order to discover the internal dynamics of the rundale agrarian commune.

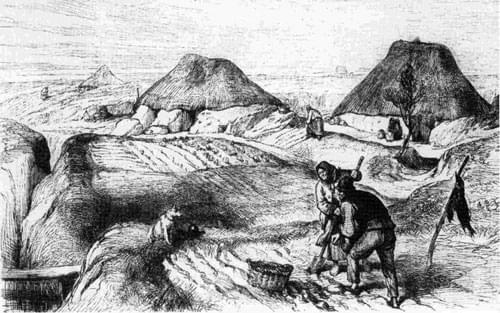

The ‘Collops’ of the Rundale.

Marx in the following comments on how concrete forms of primitive communism allocated access to differing soil fertility enclaves:

‘In fact, however, soil-types of differing grades of fertility are always cultivated simultaneously and for this reason the Germans, the Slavs and the Celts very carefully distributed scarps of lands of differing types amongst the members of the community; it was this that later made division of the community lands so difficult’ (Marx to Engels, 26th Nov. 1869).

In the case of the Irish (Celtic) Rundale commune, this distribution was organized through the use of the collop.

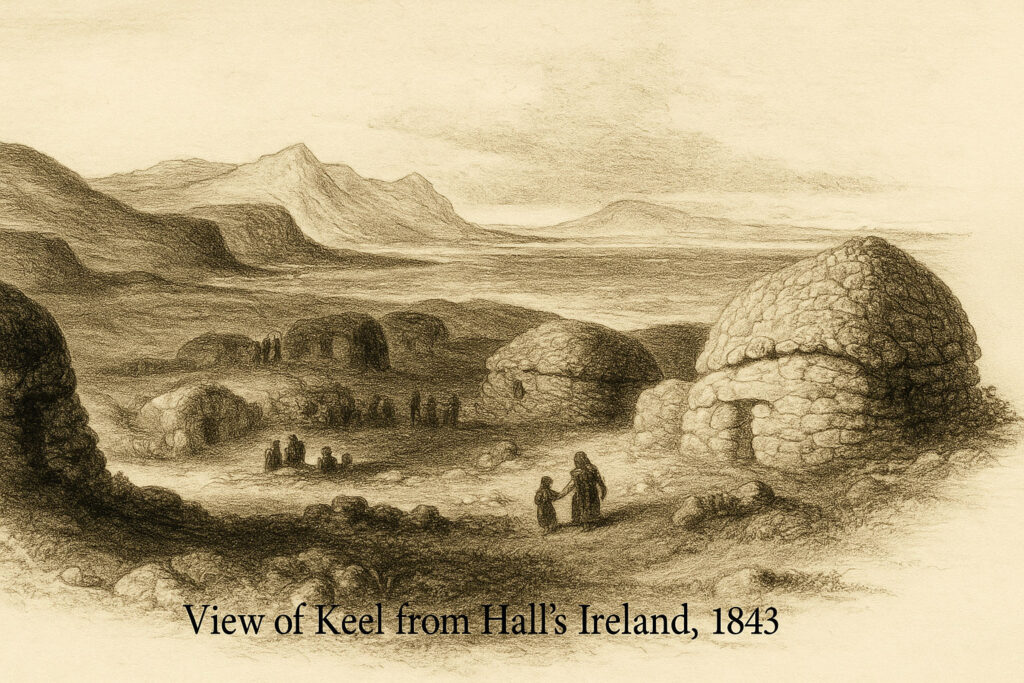

Clachans: Communal and livestock settlements of the Rundale system.

The layout of clachan settlements and houses within were characterized by their unorthodox spatial and architectural arrangements. These unconventional features may be attributable to the essential communality of the lifestyle of its residents and to their survival in inhospitable circumstances.

Livestock’ in particular cattle, played pivotal role in shaping the communal lifestyle and the physical layout of the clachans. In particular they influenced the internal design of the clachan houses.

Irish contemporary gardens and the metabolic rifts.

Reconstructing ‘Nature’ as a Picturesque theme park: The colonial case of Ireland

This article explores how a new social form of a garden aesthetic came into being in Britain and was subsequently introduced to the British colonies, including Ireland. Originally, it emerged from landscape painting and became known as the picturesque.

In gardening, the essential manifestation of the picturesque was a social form of visuality, which was an abstract compositional force which provided conventions for assessing organic entities but also for reshaping their surface countenance and established their ornamental location within these gardens of the picturesque.

This garden became known as the English informal garden, which when located in the colonies it realized itself as a spatialized colonial ideology which excluded the native and colonized people from these aesthetic theme parks.

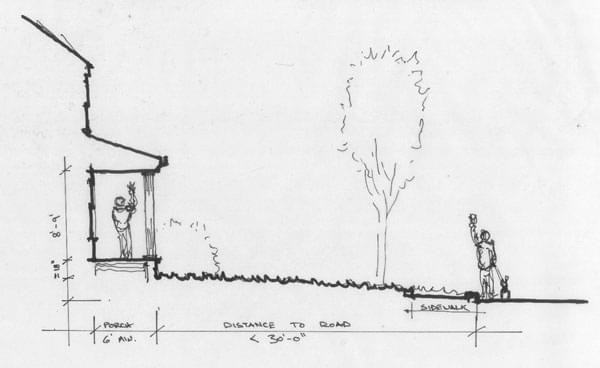

The Suburban front Garden – a spatial entity determined by social and natural processes.

This paper was written with Michael Peillon and it investigates how the suburban front garden is determined by an ensemble of diverse social and organic processes. The essential structure of these metabolizing processes is the abstract social form of visuality, which provides compositional conventions for assessing objects, both organic and inorganic, for their construction and maintenance in the suburban front garden.

The gardener uses this abstract social form of visuality to construct the concrete forms of visuality, which we identified as the prospect, panoptic and aesthetic forms. These inherent social forms are constantly challenged by the organic tendency of the plant ecosystem to grow. Therefore, beneath the surface appearance of the suburban front garden, there exists complex interconnecting relationships between nature and society.

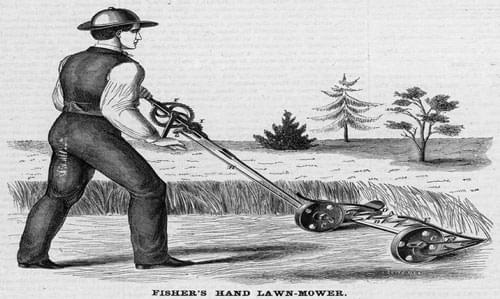

The Sprawling Global Lawns of the Emerald Isle: A Dialectical Unfolding.

This piece examines how the suburban front lawn is involved in an exchange of complex relationships between nature and society. These processes include the natural process of grass growth, the labour process of ‘improving upon nature’, the aesthetization process of harnessing nature for aesthetic designs and the commoditization process, in which organic and inorganic inputs are bought and brought into the front lawn.

This matrix of metabolizing processes can best be summarised by the idea that it is an aesthetic metabolic rift which is itself determined by the coming together of Benjamin’s process of exhibition value and Foster’s metabolic rift. This form of lawn metabolization is expressed by the concepts of the rift canopy and the aesthetic veneer and although the empirical case study is Ireland it has in fact global implications.

The corporeal and economic metabolic rifts of Irish Peasant Society.

Engels and Marx on dialectically determined reality and the dire consequences for Nature of our failure to recognize it.

The ‘bewitched’ world of everyday things: Engels and Marx on dialectically determined reality and the dire consequences for Nature of our failure to recognize it[1].

Everything that has a fixed form, such as a product, etc., appears as merely a moment, a vanishing moment, in this movement. The direct production process itself here appears only as a moment. The conditions and objectifications of the process are themselves equally moments of it, (Marx, Grundrisse, 712).

Marx on the Reciprocal Interconnections between the Soil and the Human Body: Ireland and Its Colonialised Metabolic Rifts

Marx’s writings on Ireland are widely known, but less appreciated is their centrality to the formation of his ecological thought. We show how Marx’s understanding of metabolic rift evolved in line with his writings on colonial Ireland, revealing a concept more holistic than the “classic” metabolic rift of the soil. We recover and extend this concept to the corporeal metabolic rift, showing how both are inherent in Marx’s various writings on Ireland.